Crowding Out Drives Narrowness

By Michael Wilson, Morgan Stanley's chief US equity strategist

Four years ago, I wrote a Sunday Start, The Other 1 Percenters, in which I discussed the ever-growing divide between the haves and have-nots. This divide was not limited to consumers but included corporates as well.

Fast forward to today, and it appears this gap has only gotten wider. Back then, the average company was experiencing earnings headwinds even though the economy was doing well, small caps and the average stock were underperforming the S&P 500 materially in both earnings and price terms, and the top 5 companies were dominating the market indices. Sound familiar?

Today, those divergences are even more extreme: Real GDP growth is similar to back then, while nominal GDP growth is higher due to inflation.

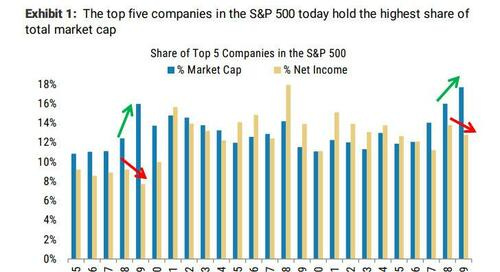

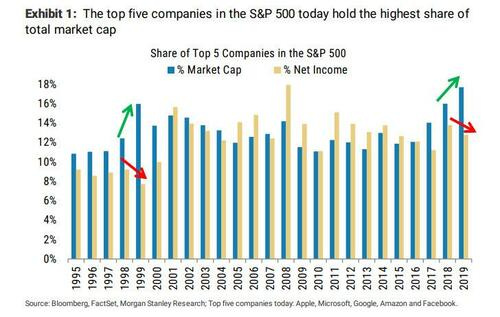

Nevertheless, the earnings headwinds are just as strong despite higher nominal GDP, as many companies find it harder to pass along higher costs without damaging volumes. As a result, market performance is historically narrow, with the top 5 stocks accounting for a much higher percentage of the S&P 500 market cap than they did in early 2020. In short, the equity market understands this economy is not that great for the average company or consumer.

In my view, the narrowness is partly due to a very unusual mix of loose fiscal and tight monetary policy with accommodative liquidity. Since the pandemic, the fiscal support for the economy has run very hot. Despite the fact we are operating in an extremely tight labor market, significant fiscal spending has continued. Since 2020, the budget deficit has averaged 9.4% of GDP. Last year, the deficit increased to 6.5% from 5.4% in 2022. While this is well below the levels reached in 2020 (15.2%) and 2021 (10.5%), it’s high considering the Federal Reserve is trying to get inflation down. In many ways, hefty government spending may be working against the Fed and could explain why the economy has been slow to respond to generationally aggressive interest rate hikes. In short, this spending appears to be crowding out the private economy and making it difficult for many companies and individuals.

The other policy variable at work is the massive liquidity being provided by the reverse repo to pay for these deficits. Since the end of 2022, this facility has fallen by over $2 trillion and is another reason why financial conditions have loosened to levels not seen since the fed funds rate was closer to 1%. This funding mechanism is part of the policy mix that may be making it challenging for the Fed’s rate hikes to do their intended work on the labor market and inflation. It may also help to explain why the Fed continues to walk back market expectations about the timing of the first cut and perhaps the number of cuts that are likely to occur this year.