Premium Subscribers Note: This is a ZH version of Weekly Part 1: The Chinese Silver Standard's Historical Journey but with strong hints at the context of where we’re going with this in the section below entitled “End of an Era” . Specifically the fall of Western pricing power in Silver and Gold.

For good measure we added in Goldman’s Kickstart for the Week ahead, and BLACKROCK's Weekly Commentary at bottom

History Repeating Itself: Exploring the Chinese Silver Standard

Columbus Started It

China Prefers Silver over Gold

The Opium Wars and the Decline of China's Sovereignty

Development of the Chinese Silver Standard

Chinese Private Banks

End of an Era

What Made Western Fiat Work?

Impact on China: Depression and the Rise of Mao

History Rhyming Now?

***Early Draft, footnotes

Mark Twain's famous words about history rhyming and not repeating itself echo the common sentiment that humans learn nothing from history. Nevertheless, it is always valuable to delve into the annals of the past.

This is particularly true in the case of the Chinese silver standard, which not only endured as one of the longest-existing coin standards but also successfully unfolded with minimal intervention from the Chinese government.Its origins can be traced to a development on the opposite side of the world: Christopher Columbus' (re)discovery of America in 1492, paving the way for Spain to rise as the first truly global power.

2- Columbus Started It

By the mid-16th century, the Spanish Empire had established the first global trade network. They brought silver from Mexico, Peru, and Chile across the Pacific to China, purchasing tea, porcelain, silk, and spices in return. The Manila Galleon served as the pivotal transshipment port, ferrying Chinese goods back to the east.

The treasures were then unloaded in Acapulco and transported overland to Vera Cruz on Mexico's east coast. From there, alongside other precious metals and New World commodities, the goods made their way to Spain through the Spanish treasure fleet.

Despite the Spanish trade system's demise in 1821 with Mexico's independence, its effects persisted through the establishment of the silver standard that endured well into the 20th century.

3- China Prefers Silver over Gold

During the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, China showed little interest in foreign goods. European products and those from European colonies overseas failed to capture the attention of the Chinese populace.

The Chinese were primarily interested in acquiring silver, which held a significantly higher relative value in their domestic economy compared to gold. The gold/silver ratio in China stood at 1:3, while in Europe, it fluctuated between 1:15 and 1:20. These European figures better reflected the natural distribution of gold and silver in the Earth's crust.

Europeans, however, were captivated by Chinese goods, particularly tea, silk, and porcelain. Spices, precious stones, and woods were also highly sought after. This created an imbalance in trade, with the Chinese amassing substantial surpluses while the Europeans, especially the Spanish and later the English, faced significant deficits vis-à-vis China.

The Spanish, buoyed by seemingly boundless silver mines in Mexico and Peru, supplied approximately half of the silver mined in the Americas from 1500 to 1821 to China. The British, however, found an unethical trade-balance solution in opium.

They heavily promoted its cultivation in Bengal and India through private merchants and smugglers. This trade strategy transformed the deficit into a massive surplus, resulting in the outflow of around 20 million silver dollars from the Chinese empire between 1820 and 1835.

The British Empire's pursuit of this economic advantage, during the struggles of Central and South American countries for independence from Spain, significantly reduced silver mining and altered transpacific trade routes.

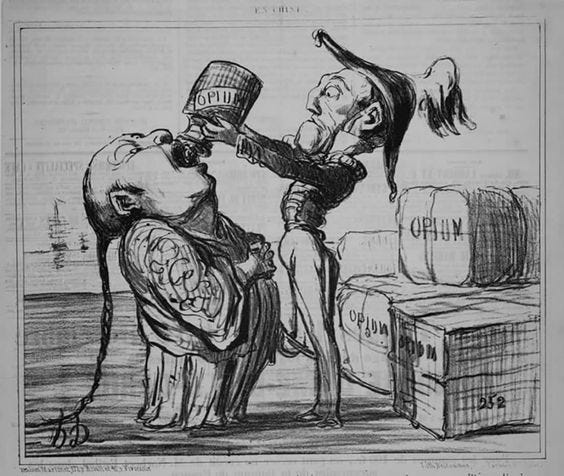

4- The Opium Wars and the Decline of China's Sovereignty

China responded to the rampant smuggling of foreign opium by aggressively cracking down on its illegal importation. While China did cultivate its own opium, mainly in the region of Guangzhou (Canton), the British Crown's monopoly in India enabled them to flood the market with vast quantities.

This created a social crisis in China, as addiction spread rapidly and its population faced an embarrassing and humiliating situation. China's attempts to curtail the opium trade ultimately led to the outbreak of the First Opium War (1839-1842), resulting in a British victory.

These events marked the beginning of a new era in China's economic and political landscape. The influx of foreign goods disrupted local industries, and the trade imbalance only widened. The Chinese government struggled to find a solution to this crisis, leading to the eventual adoption of the Chinese silver standard to curtail outflows to the UK.

5- Development of the Chinese Silver Standard

The Chinese silver standard evolved gradually, largely untouched by state intervention. As silver flowed into the country, it formed the basis of China's monetary system. The Great Tax Reform implemented by Zhang Juzheng in 1581 officially recognized silver as the standard medium of exchange.

While the Chinese silver standard existed for over three centuries, it lacked uniformity. The system relied on various coins and silver certificates, each with their own weights, shapes, and fineness. Foreign silver dollars, particularly those minted in the United States, therefore gained popularity due to standardized specifications, making them widely accepted in Chinese trade.

6- Chinese Private Banks

China's banking system also differed significantly from its European counterparts. Private banks, rather than state-controlled institutions, played a crucial role in financing trade and facilitating economic activities.

This also undermined monetary unity then. Incidentally, these private banks held considerable influence in the financial landscape and continued to play a significant role even in the early days of Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms in the late 1970s.

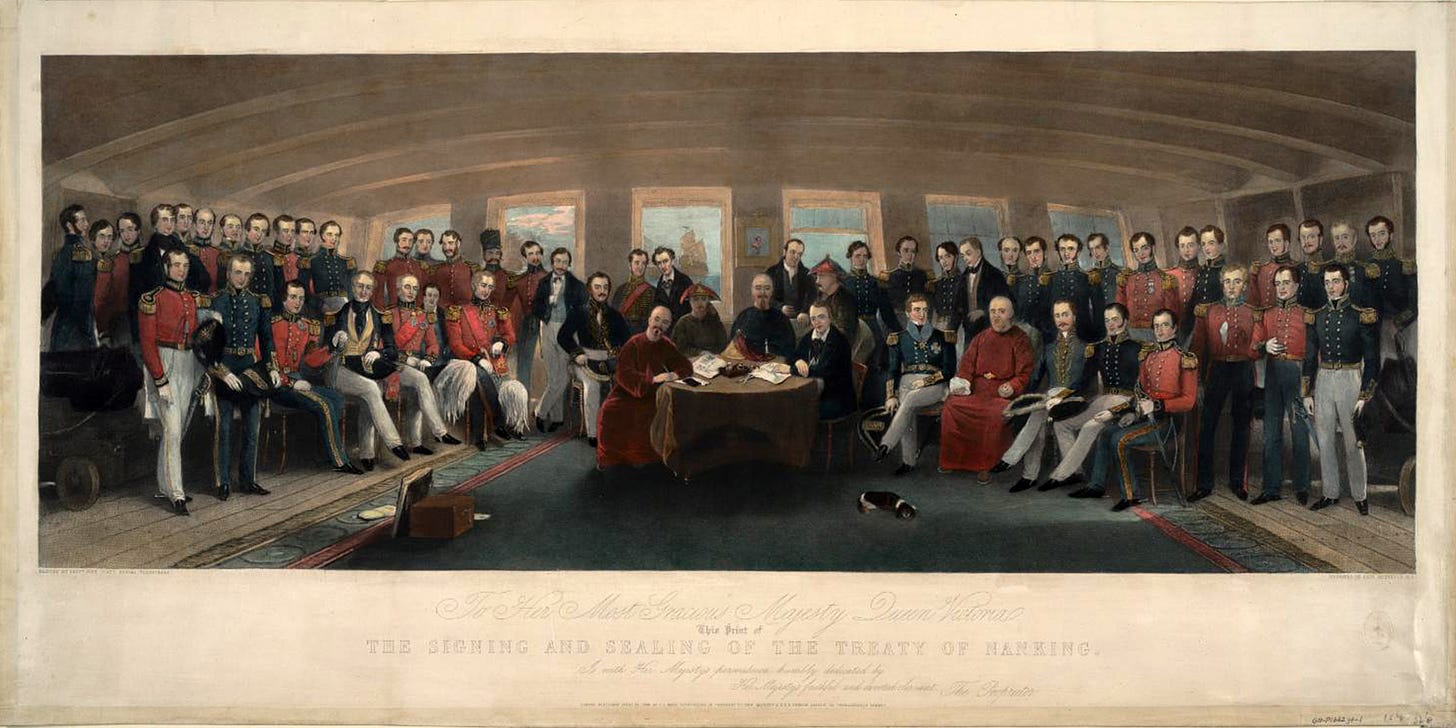

7- End of an Era

The Chinese silver standard, a monetary system that had stood the test of time for nearly 350 years, faced an abrupt and dramatic end in the early 20th century. This demise was largely influenced by external factors that significantly impacted China's monetary landscape. The external factors have one thing all in common. They represented then the rise of Global trade at the expense of Mercantilism and protectionist practices. The picture below shows how this trend has come full circle as Globalism recedes and Mercantilism (for all its faults) rises. We have contested Mercantilism is the better choice for "neutral corner" trade now as a healthy reaction to abuse of global power right now. It is certainly preferable to no-trade and global conflict.

The return of the British Empire to the gold standard1(yet another way to counter China’s continued hoarding of Silver to the UK’s detriment while the US also bought it) and the US Great Depression2, among other factors, contributed to the decline of the silver standard in China. As global economic dynamics shifted, China was forced to adapt to new monetary systems.

The rise of fiat currencies backed by the governments' credit and economic policies gained prominence worldwide. Fiat currencies, such as the U.S. dollar, were not linked to any specific commodity like silver or gold but derived their value from the trust and confidence placed in the issuing government. This departure from commodity-based currencies posed a challenge to the traditional silver standard and prompted China to adapt to new monetary systems.

8- What Made The West’s Fiat Work?

The above is extremely important when considering where we are now. How did the West pull this off, getting China’s silver standard to collapse by introducing trust/confidence-backed Fiat?

Continues here